Captain Francis D. Foley, USN

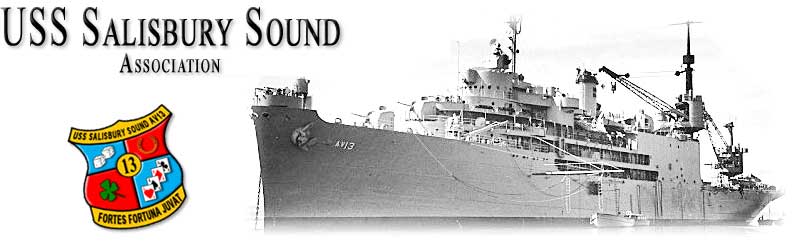

On March 19, 1955, while I was still a student at the Navy's Class A Electrician's Mate School in San Diego, the USS Salisbury Sound (AV-13) tied up to a pier at her home port at the Alameda Naval Air Station, completing her 1954-1955 Far Eastern Cruise.

All that was unknown to me at the time, of course, but a few weeks later, on April 8, 1955, I graduated from A School, and, along with my fellow graduates, was placed before a chalkboard containing a list of possible duty stations.

The top ranking graduates got first pick, and they proceeded to pick off all the glamour ships like destroyers, cruisers and aircraft carriers. Since my buddies and I had been more interested in the night life of San Diego than in studying, by the time it got down to us, the pickings were slim.

"Okay, Medland, what's it gonna be?" the old chief said, waving his hand over the few remaining ships. For some reason, the chief had seen something in me that I hadn't seen in myself, and had tried to teach me a few things without much success. I noticed that his hand hovered over the USS Salisbury Sound (AV-13).

"What the heck is an AV," I whispered out of the corner of my mouth to one of my equally challenged friends sitting beside me. "Beats me," he said, "but after that, there ain't much left."

"I guess I'll take the Salisbury Sound," I said.

"Good choice," the chief said with a twinkle in his eye.

I thought he was kidding at the time because he hadn't said that to anyone else, but the old chief knew something that the hot shots who had selected the glamour ships didn't know and that I only came to realize much later: The Salisbury Sound was great duty and I had lucked into it.

So a day or two later, with orders in hand, I found the ship tied up to that same pier at the Naval Air Station in Alameda, California, only recently returned from Buckner Bay, Okinawa. I arrived late at night and could barely make out the AV-13 painted on the hull. I stumbled up the gang plank with my sea bag on my shoulder, rehearsing what I would say when I got to the quarterdeck.

Whatever I said must have been okay, because the OOD nodded me aboard. He looked over my orders and a sailor appeared to take me below and help me find a rack. The Sally was a big ship and I felt pretty disoriented, but electricians are an easy going bunch and I soon felt right at home. I settled in and spent the next several months learning what a seaplane tender was all about.

On August 6, 1955, we had a Change of Command Ceremony on the hanger deck in which Captain Francis D. Foley, USN, relieved Captain Carson Hawkins, USN, as Commanding Officer of the Sally. I don't remember much about Captain Hawkins, but Captain Foley made an immediate impression on me. He wasn't a physically large man, but he had bright, penetrating eyes and a warm, open smile. He was clearly a leader who commanded respect.

I continued to learn about the ship and see as many of the local sights that I could work in. One night while coming back from liberty, I was walking down the pier toward the Sally, and was struck by the image of the ship, tied up to the pier and ablaze with golden lights. It's a picture I can still see clearly in my mind to this day. I have no idea what triggered it, but at that moment the idea for a novel began to form in my mind. Where the notion of writing a novel came from, I had no idea, since I had never written anything longer than a school paper before in my life. I tucked the idea away in a corner of my brain and told myself that I would do that someday.

On September 23, 1955, the ship set sail for the 1955-1956 Far Eastern Cruise that would keep us out of the country until April 12, 1956. First stop: Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The adventure of a lifetime had begun.

One day during the cruise, I was ordered to the Captain's Cabin to fix an electrical problem. As electricians, we pretty much had the run of the ship, but the Captain's Cabin was off limits to everyone. I wasn't even sure where it was. So I grabbed some tools and nodded to a friend to come along, mostly for moral support.

After roaming around in Officer's Country for a while, we found the Captain's Cabin and hesitantly stepped inside. To our relief, it was empty. My friend, who was obviously not as curious as I was, went right to work on the captain's electrical problem, while I just stood there looking around in wonder at the plush surroundings. A beautiful wooden chest of drawers caught my eye. (Beautiful furniture on a U.S. Navy ship wasn't something you saw every day.) Sitting atop the chest of drawers was a book. I stepped forward and picked it up. It was a cruise book from another ship.

I flipped through the pages. "Man," I said to my friend, who was working away, and minding his own business, "this is great. I hope we have one of these."

"We will, son. We will," a gentle voice said behind me. I turned around and there stood Captain Foley, wearing the warmest smile I had ever seen.

Caught red-handed minding the Captain's business instead of my own, it was a tense moment for an 18-year old E-3, but Captain Foley's gracious manner put me instantly at ease.

My friend and I went on about our business, and the Captain went on about his. True to his word, at the end of the cruise, we had our book. It was from that 1955-1956 Far Eastern Cruise book that I was able to scan the picture of Captain Foley that appears at the top of this page.

Decades later, I went on to write that novel, titled Point of Honor. When it was published and became a national bestseller, I decided, on a whim, to send a copy to Captain (now Admiral) Foley. I wrote him a letter, which you can read here, and sent him a signed copy of the book. I knew that he was quite elderly and never expected him to reply, but he did. You can read his gracious response here, beautifully composed and personally typed. He was almost 88 at the time, and as you can see in his letter, was going through his papers, preparing for the inevitable.

Admiral Foley died the following year on November 8, 1999, in Annapolis, Maryland, at the age of 89. He was buried with full military honors in Arlington National Cemetery. It was a fitting tribute. Born on the 4th of July into a Navy family, and named after a famous Naval hero, Admiral Francis Drake Foley dedicated his life to serving his country. He was a true American patriot. We honor his memory.

REAR ADMIRAL FRANCIS DRAKE FOLEY, USN (Ret.)

Francis Drake Foley, 89, a retired Navy rear admiral who served aboard aircraft carriers in the Pacific during World War II and later commanded Task Force 77 in the Pacific, died of heart ailments November 8, 1999 at Anne Arundel General Hospital in Annapolis, Maryland.

Admiral Foley, a naval aviator, was the air operations officer aboard the carrier Hornet when it was sunk in the Battle of Santa Cruz in the Solomon Islands in October 1942. Later in the war, he held staff positions on other carriers.

In the postwar years, Admiral Foley held assignments in Washington and elsewhere in the United States. He graduated from the Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island. In the mid-1950s, he commanded the seaplane tender USS Salisbury Sound (AV-13), and later the aircraft carrier USS Shangri-La (CVA-38) in the Pacific. He later served on the staff of the commander in chief in the Pacific in Pearl Harbor.

Other assignments were on the staff of the Chief of naval operations and at NATO headquarters in Europe.

In 1960 and 1961, Admiral Foley commanded Task Force 77, the attack arm of the Pacific Fleet.

In subsequent assignments, he commanded the 3rd Naval District in New York and served as senior member of the U.N. Command Military Armistice Commission in Seoul. He retired in 1972.

Admiral Foley was born into a Navy family in Dorchester, Massachusetts. He graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis in 1932, and he returned to Annapolis when he retired.

His military decorations included the Legion of Merit, the Bronze Star with Combat "V" and the Joint Services Commendation Medal.

He was a member of the U.S. Naval Academy Alumni Association, the Annapolis Yacht Club, the New York Yacht Club, the Army-Navy Club and the Army Navy Country Club.

His first wife, Martha McCullough Foley, died in 1965. His second wife, the former Clair O'Neill Vogel, died in 1984.

Survivors include a daughter from his first marriage, Josephine Drake Foley of Warrenton; four stepchildren, retired Navy Capt. Raymond W. Vogel of New London, Conn., retired Navy Cmdr. Timothy J. Vogel and Jamie H. Fallon, both of Annapolis, and retired Marine Corps Col. Frederick J. Vogel of Herndon; 12 grandchildren; and seven great-grandchildren.

FOLEY, FRANCIS DRAKE, RADM, USN (Ret.)

USNA Class of 1932

Of Annapolis, MD, on Monday, November 8, 1999, at Anne Arundel Medical Center. Husband of the late Martha Foley and the late Claire O'Neil Vogel Foley; father of Josephine Drake Foley of Warrenton, VA; step-father of Capt. Raymond W. Vogel, USN (Ret.) of New London, CT, CDR Timothy J. Vogel, USN (Ret.) of Annapolis, MD, Col. Fredrick J. Vogel, USMC (Ret.) of Vienna, Austria and Jamie H. Fallon of Annapolis, MD.

Also survived by 12 step-grandchildren, seven step-great-grandchildren, one niece and two nephews. Mass of Christian Burial will be offered on Friday, November 12, 11 a.m. at St. Mary's Catholic Church, 109 Duke of Gloucester St., Annapolis, MD 21401. Interment with Full Military Honors will be held Friday, November, 26, 1 p.m. at Arlington National Cemetery (friends to assemble at Administrative Building). In lieu of flowers, contributions may be made to St. Mary's Catholic Church Building Fund.

RADM Foley was a Charter Member of the USS Salisbury Sound Association (C100) and was active in the association in the mid to late 80s. He was the featured speaker at our Charleston reunion and attended others. Following is an article by RADM Foley that appeared in the December, 1998, edition of Naval History.

Why We Call a Ship a She

By Rear Admiral Francis D. Foley, U.S. Navy (Retired)

Naval History, December 1998

A salty retired U.S. Navy flag officer shuns the current trend toward political correctness. Ships are referred to as “she” because men love them, but this encompasses far more than just that. Man-o'-war or merchantman, there can be a great deal of bustle about her as well as a gang of men on deck, particularly if she is slim-waisted, well-stacked, and has an inviting superstructure. It is not so much her initial cost as it is her upkeep that makes you wonder where you founder.

She is greatly admired when freshly painted and all decked out to emphasize her cardinal points. If an aircraft carrier, she will look in a mirror when about to be arrested, and will wave you off if she feels you are sinking too low or a little too high, day or night. She will not hangar around with duds, but will light you off and launch you into the wild blue yonder when you muster a full head of steam.

Even a submarine reveals her topsides returning to port, heads straight for the buoys, knows her pier, and gets her breast-lines out promptly if she is single-screwed. On departure, no ship leaves port asleep, she always leaves awake. She may not mind her helm or answer to the old man when the going gets rough, and can be expected to kick up her heels on a family squall. A ship costs a lot to dress, sometimes blows a bit of smoke, and requires periodic overhauls to extend her useful life.

Some have a cute fantail, others are heavy in the stern, but all have double-bottoms which demand attention. When meeting head-on, sound a recognition signal; whistle! If she does not answer up, come about and start laying alongside, but watch to see if her ship is slowing . . . perhaps her slip is showing? Then proceed with caution until danger of collision is over and you can fathom how much latitude she will allow.

If she does not remain on an even keel, let things ride, feel your way, and do not cross the line until you determine weather the “do” point is right for a prolonged blast. Get the feel of the helm, stay on the right tact, keep her so, and she will pay off handsomely. If she is in the roaring forties, however, you may be in the dangerous semi-circle, so do not expect much “luff,” especially under bare poles. She may think you are not under command or control and shove off.

If she edges aweigh, keep her steady as she goes, but do not sink into the doldrums. Just remember that “to furnish a ship requireth much trouble, but to furnish a woman the cost is double!” To the women who now help us “man” our ships, my apologies for the foregoing. Only the opening phrase presents my true feelings. After all, a ship's bell(e) will always remain her most prized possession, and every good ship has a heart, just like yours.

A trick at the wheel, like you, would have been welcome aboard when I was on “she” duty for 40 years. May God bless you all, sweetheart!

Good Point! At Naval History's editorial offices, in the presence of the author, the editor reacted to the above with a resounding: “Most of our readers will love it; the women will hate it!” Coincidentally, the U.S. Naval Institute's chief financial officer, obviously sensitive to such statements, overheard and inquired: “The women will hate what?” She then heard of plans to publish “Why We Call a Ship a She.” Unaware of the author's presence, she asked: “If they call ships she, then why do they name them Arleigh Burke?” To that, Admiral Foley responded, “Good point!”

YNCS Don Harribine, USN(ret)

life worthwhile in their lifetime....can respond with a great deal of pride and

satisfaction, “I served a career in the United States Navy.”